I’ve read all the articles and listened to all the podcasts about procrastination. I’ve tried all the tricks—including literally trying to trick myself.

Sometimes hacks work. Sometimes an article about how bad a habit procrastination is will kick me into gear and help me get things done early for a change.

But it never lasts. I’ve never fully kicked procrastination to the curb. Even when I’m on a productive bent, I’m still a procrastinator at heart.

When I’d just about given up on ever curing my bad habit, I came across a theory of procrastination I’d never heard of, and it completely changed the way I think about procrastination.

The truth is, procrastination is more about our emotions than our tendencies for laziness or just being “bad at deadlines”. At its core, we procrastinate to keep ourselves happy in the moment —which makes complete sense, right? That is, until we’re pulling an all-nighter to meet that client deadline we had weeks to prepare for.

Understanding why we procrastinate allows us to develop effective strategies for getting started on our important projects now, rather than waiting for tomorrow. Here’s what I’ve discovered in my own journey to stop putting things off for later, and the concrete steps I’ve found along the way to address the root cause of my procrastination.

Why we procrastinate

Procrastination is thought to come from an emotional reaction to whatever it is you’re avoiding. Researchers call this phenomenon “mood repair”, where we avoid the uncomfortable feelings associated with our work by spending time on mood-enhancing activities, like playing games.

As Timothy Pychyl, an associate professor of psychology at Carleton University, explained it “putting off the task at hand is an effective way of regulating this mood. Avoid the task, avoid the bad mood.”

Of course, the mood lift is inevitably short-term. Studies of college students have found the habit of putting things off only increases negative feelings later on. While procrastinators tended to be less stressed and healthier in the first school term, by the second term these results were actually reversed.

This brings us to the second key insight into why we procrastinate: research shows that our brains are actually wired to think about about our present and future selves as two separate people. That’s why we’re able to prioritize our present mood at the expense of our future well-being even though it’s an irrational choice in the long-term.

A study run by UCLA psychologist Hal Herschel and a team at Stanford University found that participants actually engaged different areas of the brain when they thought about their present selves versus their future selves. In fact, when people were told to think about themselves in ten years, their brain patterns closely resembled those observed when they were asked to think about celebrities they didn’t know.

This separation of present and future self encourages us to make different decisions about ourselves now and in the future. For instance, one study showed people asked to tutor other students would offer to do so less in the present, but would offer more of their time in the future.

To sum up the research, we procrastinate because our brains are wired to care more about our present comfort than our future happiness.

So what can we do about it?

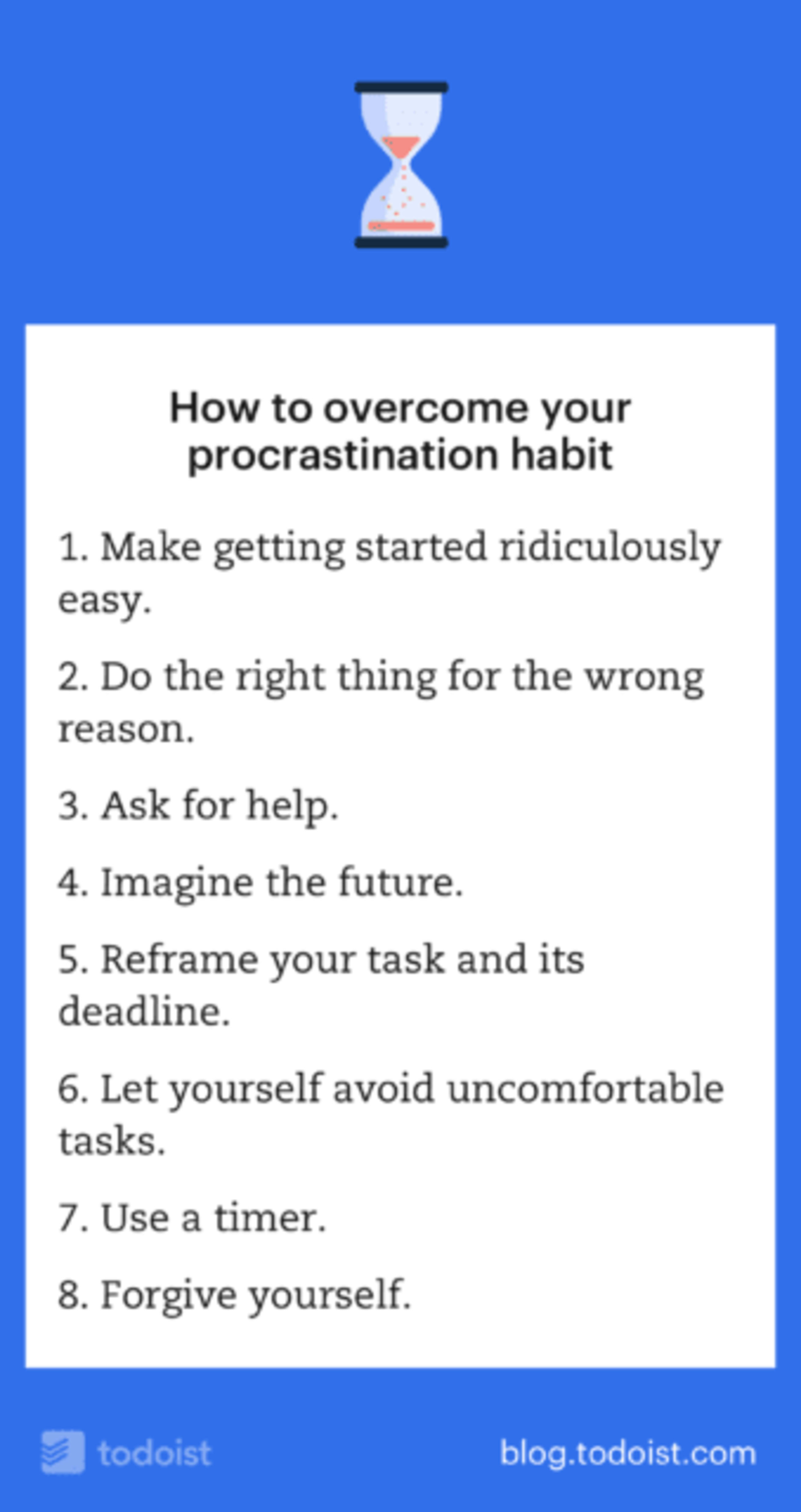

How to overcome your procrastination habit

Based on the research, it’s clear that we have two ways of dealing with our procrastination:

- Make whatever we’re procrastinating on feel less uncomfortable, and

- Convince our present selves into caring about our future selves.

Here are 8 concrete strategies you can start using today to address the root cause of your procrastination...

1. Make getting started ridiculously easy

To overcome our psychological aversion to uncomfortable tasks, Dr Pychyl suggests “[making] the threshold for getting started quite low” and just getting started. Often starting a task is the biggest hurdle.

For example, Dr. Pychyl says “A real mood boost comes from doing what we intend to do—the things that are important to us”. Knowing this, we can reason that although getting started might feel uncomfortable, we’re likely to feel much better once the task is done. Compare the mood boost of having done what you intended to do, to the disappointment and frustration of dealing with the consequences of procrastination later.

In fact, research shows that progress—no matter how small—can be a huge motivator to help us keep going.

My favorite trick for getting into a task I’m dreading, is to start with the mindset. I start by just thinking about the task for a while, until I’m drawn in and can’t help working on it.

If it’s a writing task, I might pull up the draft I need to edit and just sit and read over it. Soon I’ll find myself changing a word here and there, or fixing typos. Then I’ll think of a whole sentence I want to add. And suddenly I’m well into the task, without really pushing myself to do so.

If it’s coding I need to work on, I do a similar thing. I open the project in Xcode and just look at it for a while. My brain starts to get into the coding mindset as I read over what I’ve written before. I ease myself into the right mindset for this project just by gently immersing myself in it at first. Then I might remove or add a comment, or make a small change to the code. And before I know it I’m stuck into the work I need to get done.

Poet and author Mark McGuinness used this method to write a book:

A few months ago I just created a file in my book writing software and laid out the chapter headings, and just started playing around and rearranging them. And each time an idea came to me during the day, I just added a quick note inside each chapter. Recently I’ve been opening up the doc in the mornings, just looking at the table of contents, and just adding a few more notes here and there. It’s a slow ramp up where I just tell myself to add a few things here and there, no pressure.

When McGuinness wrote that paragraph, he’d already written 12,000 words of his book. “I haven’t really started writing it yet,” he said. “And since I’ve not been officially working on the book, resistance and procrastination hasn’t shown up for work either. It’s been fun.”

If it helps, you can also try using a timer for this approach. Set the timer for just 5 or 10 minutes. While the timer’s running, you don’t have to work, but you can’t do anything else. You have to sit with your work, even if you don’t get started. Personally, I’d rather work than do nothing at all, so I wouldn’t even last five minutes before this trick made me get started.

2. Do the right thing for the wrong reason

Since negative emotions are the cause of our procrastination, what if we could manage our negative emotions while working? Behavioral economist Dan Ariely calls this method reward substitution, while Katherine Milkman, also a behavioral economist, calls it temptation bundling.

Reward substitution, as described by Ariely, is essentially getting yourself to do the right thing for the wrong reason. The reason this works is because, according to Ariely, humans aren’t wired to care about things that will happen far into the future. While it would be in our best interests to think about the future, we’re focused on what makes us feel good now. This makes it hard to do unpleasant things which would benefit us in the future.

Ariely uses global warming as an example of a future problem. It’s hard to care about global warming because we don’t see the signs of it regularly, we don’t see people suffering, and it’s not going to affect us seriously until far in the future. But if you feel self-important when you drive a Toyota Prius, because it makes you feel like you’re a good person, and it shows others that you’re a good person, then you might be more likely to do so. You’d be doing the right thing (switching to a hybrid car) for the wrong reason (your self-image).

Ariely shares another story that illustrates this principle at work. When he contracted Hepatitis C in the hospital, he was put on an 18-month treatment plan. Three times every week for the whole 18 months, Ariely had to inject himself with a drug that treated his Hepatitis, but also made him nauseous and induced fever and vomiting.

Those horrible side effects made it hard for Ariely to do the right thing (inject the drug) on a regular basis, for a good result that was far in the future. The way he got around this, and managed to stick to the 3x/week schedule for the whole treatment period was to find a reward that took effect immediately. Ariely is a big movie fan, so he stopped watching movies any other day of the week, and saved up 2–3 films to watch every day he had to inject the drug. Immediately after the injection, before he started to feel the side effects, Ariely rewarded himself with starting his movie marathon.

Because his action was rewarded in the now every time, Ariely continued to do the right thing (inject the drug) for the wrong reason (so he could watch movies).

I’ve tried this myself in the past. I got hooked on the first season of the Serial podcast, which had new episodes released once per week. I never listened to Serial except when I was running, so whenever a new episode was released, I would get excited about going for a run (doing the right thing) because it meant I could listen to Serial (the wrong reason)—rather than because running is good for my health and fitness (the right reason).

3. Ask for help

When my work directly affects others, I find it much harder to accept the consequences of procrastinating.

To put this into practice, you could ask a friend or colleague to help you get started on something you’ve been putting off. Having someone else work with you can stave off the boredom and loneliness that make working alone a drag. And having someone else invested in the work can give you extra motivation to get it finished, even if they’re not around the whole time you’re working on it.

This can be particularly helpful when you’re stressed. Research has shown discussing your feelings of stress with someone else in a similar emotional state can ease your feelings of stress. So if you’re working with other people and you’re all worried about an upcoming deadline, try discussing the situation rather than internalizing your own concerns.

One MetaFilter user goes a step further with getting help from others:

In an emergency I actually get my husband to sit down with me and my laptop and he makes me explain to him what I want to say, watches me type it out, and then makes me explain the next part, and so on. Literally paragraph by paragraph. It stops me wandering off topic or getting distracted.

Although this seems extreme, a sympathetic colleague, mentor, friend, or sibling might be willing to help out if you don’t always rely on this approach.

4. Imagine the future

Although Ariely says we’re geared to think about now, and not the future, some studies have shown encouraging people to imagine the future can help them make better decisions now.

Pychyl calls this method “time travel”. He suggests, for instance, imagining as vividly as possible the idea of living on your current retirement savings, if saving for retirement is something you’ve been putting off.

Unfortunately, Pychyl suggests we may procrastinate on this task itself, which he calls second-order procrastination—procrastinating on tasks that would help us overcome our procrastination. Pychyl also worries the emotional reaction of the time travel method, which helps spur us into action, may wear off over time.

Making the task of time travel more concrete can help its effectiveness. Pychyl suggests looking at a digitally aged photograph can help us more effectively imagine ourselves in the future, thus helping us make better decisions.

Another way to use this method is to realistically imagine how you’ll feel tomorrow, if you’re trying the old “I’ll feel like doing this tomorrow” excuse. Pychyl says it’s highly unlikely we will feel more motivated tomorrow so time traveling may help us realize this, and stop relying on the “tomorrow” excuse.

5. Reframe your task and its deadline

Have you ever tried to trick yourself to get your work done? I tried this many times—my favorite approach was to pretend my deadline was actually today, not tomorrow, so I’d get started earlier.

But it never worked.

I just couldn’t get past the fact that I was trying to lie to myself. The rest of my brain knew what I was saying was a lie, so why would that ever work?

Science backs me up here. Research by Ariely and his co-author, Klaus Wertenbroch, found external deadlines work better than deadlines we impose on ourselves.

Another study of procrastination found reframing the task itself, rather than adjusting its deadline, was effective in helping procrastinators get to work. Participants in this study were asked to complete a puzzle, but were allowed to play Tetris for a while first.

When the puzzle was described as “cognitive evaluation”, procrastinators spent more time playing Tetris and avoiding the puzzle. When the puzzle was introduced as a game, however, the chronic procrastinators in the study got sucked into the puzzle as quickly as anyone else.

You might not always be able to convince yourself that your work is a game, but look for ways to reframe it.

I use this approach by reframing my task into a challenge. I say to myself, “Can you get this work done today, so that you have tomorrow free to do whatever you want? Go on, try it”. Or, “Hey, what if you got this work done before lunchtime? You could go out somewhere new for lunch and not even worry about doing more work when you get home. Go for it!”

My competitive nature wakes up when I give it a challenge. I like the idea of proving something, so this is a good way to “trick” my brain into getting stuck into some work I’ve been avoiding.

One approach I picked up from a MetaFilter suggestion is to challenge yourself to stay focused on a single task for as long as possible:

… try a count-up timer. See how long you can remain on task. See if you can beat your last record…

Here’s a really simple stopwatch you can use for free in your browser to apply this approach.

Another way I reframe work is to do it away from my desk. Although I have a great set up with a big screen and an ergonomic chair, there’s no way to tell myself I’m not about to work hard if I sit at my desk. But when I take my laptop to the kitchen table, or lie in bed with my iPad to write, it’s a lot harder to believe I’m doing “real work”.

Pychyl also suggests changing your attitude toward the task. If you think of your task as something you have to do, it’s likely that you’re feeling external pressure to get it done—it’s something expected of you, and the motivation to get it done is external. “External motivation requires self-control to be successful,” says Pychyl. “We have to exert our will to get down and work at the task as intended.”

Internal motivation, on the other hand, doesn’t cost us. We still have to exert ourselves to get the work done, but if we’re working from internal motivation it won’t feel draining. Pychyl suggests thinking of your task as something you want to get done, to help adjust your motivation to be more internal. When you care about getting something done for your own sake, rather than a deadline or external expectation, you can more easily find the effort required to get started.

6. Let yourself avoid uncomfortable tasks

If you can’t stop procrastinating, the good news is you can use this “bad” habit to your advantage. “Structured procrastination” is a clever way to stay productive even while you procrastinate.

John Perry wrote about this technique at structuredprocrastination.com, calling it “an amazing strategy I have discovered that converts procrastinators into effective human beings, respected and admired for all that they can accomplish and the good use they make of time”. According to Perry, the key to understanding structured procrastination is recognizing “that procrastinating does not mean doing absolutely nothing”.

Here’s how it works: next time you feel the urge to procrastinate, go for it. Avoid that Big Scary Task that makes you feel really uncomfortable. But instead of spending time on Reddit or watching Netflix, work on something else productive. Choose anything else from your task list, and spend your time procrastinating by working on a less important or urgent task that makes you feel less uncomfortable.

Although this doesn’t stop the Big Scary Task from needing to be done, it does assuage some of the guilt that comes from procrastination, because you’re actually spending your time productively.

Perry also makes an important note: as self-aware procrastinators, we tend to cut down our to do lists. We know we’re not good at getting things done, so we think having fewer things to do will help. According to Perry, this goes against our nature as procrastinators. “The few tasks on [your] list will be by definition the most important,” he says, “and the only way to avoid doing them will be to do nothing. This is a way to become a couch potato, not an effective human being”.

Investor and entrepreneur Paul Graham uses the term “good procrastination” to mean working on more important things than what you’re avoiding. He says working on errands or unimportant tasks to avoid your real work is “bad procrastination”, whereas “good procrastination” is avoiding errands to do real work:

When I talk to people who’ve managed to make themselves work on big things, I find that all blow off errands, and all feel guilty about it. I don’t think they should feel guilty. There’s more to do than anyone could. So someone doing the best work they can is inevitably going to leave a lot of errands undone.

Graham breaks procrastination into three types, depending on what you do instead of that Big Task you’re avoiding:

- You do nothing

- You do something less important

- You do something more important

The trick to “good procrastination”, according to Graham, is avoiding the less important, more urgent things on your to do list (which he suggests may be everything on it) to work on really important work. Your next big idea. The book you keep saying you want to write. The side project you believe in, but can’t find time for.

This is real work, says Graham. Mowing the lawn and filing your taxes can wait, if it means you spend big chunks of time on work that matters.

7. Use a timer

Zen habits blogger Leo Babauta uses timers when he’s struggling with procrastination.

First, Babauta sets a timer for 30 minutes. During that time he stays focused on his work. When the timer goes off, he sets it again for 10 minutes, and rewards himself with a fun activity like blogging, reading emails, or checking RSS feeds. You could substitute YouTube videos, chatting with friends, or reading a book.

After 10 minutes, Babauta resets his 30-minute timer and gets back to work.

This method only works if you’re willing to stick to the timer schedule, so try to be really strict when you first try it out. And make that reward something you really look forward to, so you’re willing to stay focused in-between the 10-minute breaks.

This probably sounds similar to the Pomodoro Technique. If you haven’t heard of it, Pomodoro works with a simple kitchen timer (a timer on your phone or computer can work, too). You set the timer for 25 minutes, work until it goes off, then take a 5-minute break.

After four rounds of 25-minute work chunks, you can take a longer break of 15–30 minutes.

Lots of people swear by this method, but I’ve always found it a bit restrictive. None of my tasks fit neatly into 25 minutes, and the 5-minute break doesn’t feel long enough to refresh my mind and stop thinking about what I’m working on.

To get around this, I use a slightly altered version of the Pomodoro Technique, which I call “Real Life Pomodoro”. Rather than using a timer set to 25 minutes, I use real-life events as timers.

For instance, because I work from home, I might put on the washing machine or dishwasher. While I wait for the machine to finish, I get to work on something I’ve been avoiding. Knowing I only have to work until the washing is done makes it easier for me to get stuck in—for some reason a time limit makes hard tasks seem less confronting.

And once the machine is finished, I unpack the dishwasher or hang up the washing. This takes me completely away from my work for a little while, and I get to do something more physical, so my body gets a break. I find this refreshing, and it helps me stay on top of housework at the same time!

You can make a real-life pomodoro from anything, but here are some more ideas of events you could use as timers:

- Waiting for a download to finish

- Waiting for someone to arrive at a meeting

- Waiting for a phone call, or waiting on hold

- Waiting for food to finish cooking

- Trying out a new album or playing a favorite playlist

- Waiting for a train or bus

- Waiting for your phone or computer to install updates and restart

8. Forgive yourself

A 2010 study of university freshman found that participants who forgave themselves after procrastinating on studying for the first exam in a course were less likely to procrastinate on studying for later exams. The researchers believe forgiving yourself for procrastinating can help you overcome negative feelings about the work you’ve put off in the past, so you can more easily approach future tasks.

Dr Pychyl, who was a co-author of this study, says self-forgiveness is “typically accompanied by a vow to change one’s behavior in the future,” which makes it more likely that we’ll procrastinate less after forgiving ourselves for procrastinating in the past. Pychyl also notes that the self-forgiveness effect is most noticeable in students who reported high levels of procrastination on their first exam. Pychyl says this is probably because “low levels of procrastination are unlikely to be perceived as having had much of an effect on one’s performance,” and therefore require less self-forgiveness.

When your confronting a daunting task, procrastination can seem almost inevitable. It’s not something most people can just decide to stop doing through sheer force of will. But understanding why we’re prone to procrastination and how to work with that habit, or around it, can help us avoid the worst consequences of avoiding work.

Have you discovered any strategies that have helped you overcome a procrastination habit? Share your experience with the rest of us procrastinators in the comments below!