If you’ve ever worked closely with someone else in a work environment (so pretty much everyone), you’ve had a disagreement. Maybe you didn’t agree with the current approach for tackling a project, or you weren’t quite sold on the marketing of a new product. Either way, you didn’t quite see eye to eye with the other party.

Disagreement is healthy, even critical, for success. It’s the hallmark of an engaged and involved team member. It’s essential for testing and improving new ideas. It’s an opportunity to build trust, respect, and mutual understanding. If your team isn’t disagreeing, there’s a good chance you have a different kind of problem on your hands.

Thoughtful disagreement truly is an art. When mastered, you’ll be able to express your opinions without shutting down the discussion or angering the other side. It involves listening more, changing your perspective on disagreement, and learning how to better structure your arguments.

You are not your idea.

Ed Catmull is the president of Pixar and Walt Disney Animation Studios. At Pixar, Catmull has worked diligently to create a culture where it’s perfectly acceptable (and encouraged) to thoughtfully disagree with one another. Everyone feels comfortable stress-testing the ideas of the group. That’s how innovative masterpieces like Toy Story, Up, Wall-E, and Inside Out get made.

To create this kind of culture, Catmull established a group known as the Braintrust that meets regularly to review movie progress and provide honest feedback. In his book Creativity, Inc, Catmull describes a core tenant of thoughtful disagreement — avoid identifying too closely with your ideas:

“You are not your idea, and if you identify too closely with your ideas, you will take offense when they are challenged.”

This is echoed by William Ury in Getting Past No, his insightful guide to tricky negotiations. In the book, Ury describes four common reasons that your counterpart in a disagreement may fail to agree with you. Reason #1: Fear of losing face. “No one wants to look bad to his or her constituents.”

If you identify too closely with your idea, if it becomes a core tenant of who you are and what you believe in, you’re headed for trouble. The trick is to balance passionate conviction with realistic expectations. If your idea doesn’t get adopted, that’s not a personal attack on you; there must have been an equally good — or even better — way than the one you envisioned. The sooner you can disassociate yourself from your idea, the better you’ll be able to disagree without sabotaging the discussion with your emotions.

What are we actually disagreeing about?

In his book Principles, investor Ray Dalio describes a scenario he sees frequently at Bridgewater Associates, one of the largest and most successful hedge funds in the world:

“I’ve seen people who agree on the major issues waste hours arguing over details. It’s more important to do the big things well than the small perfectly.”

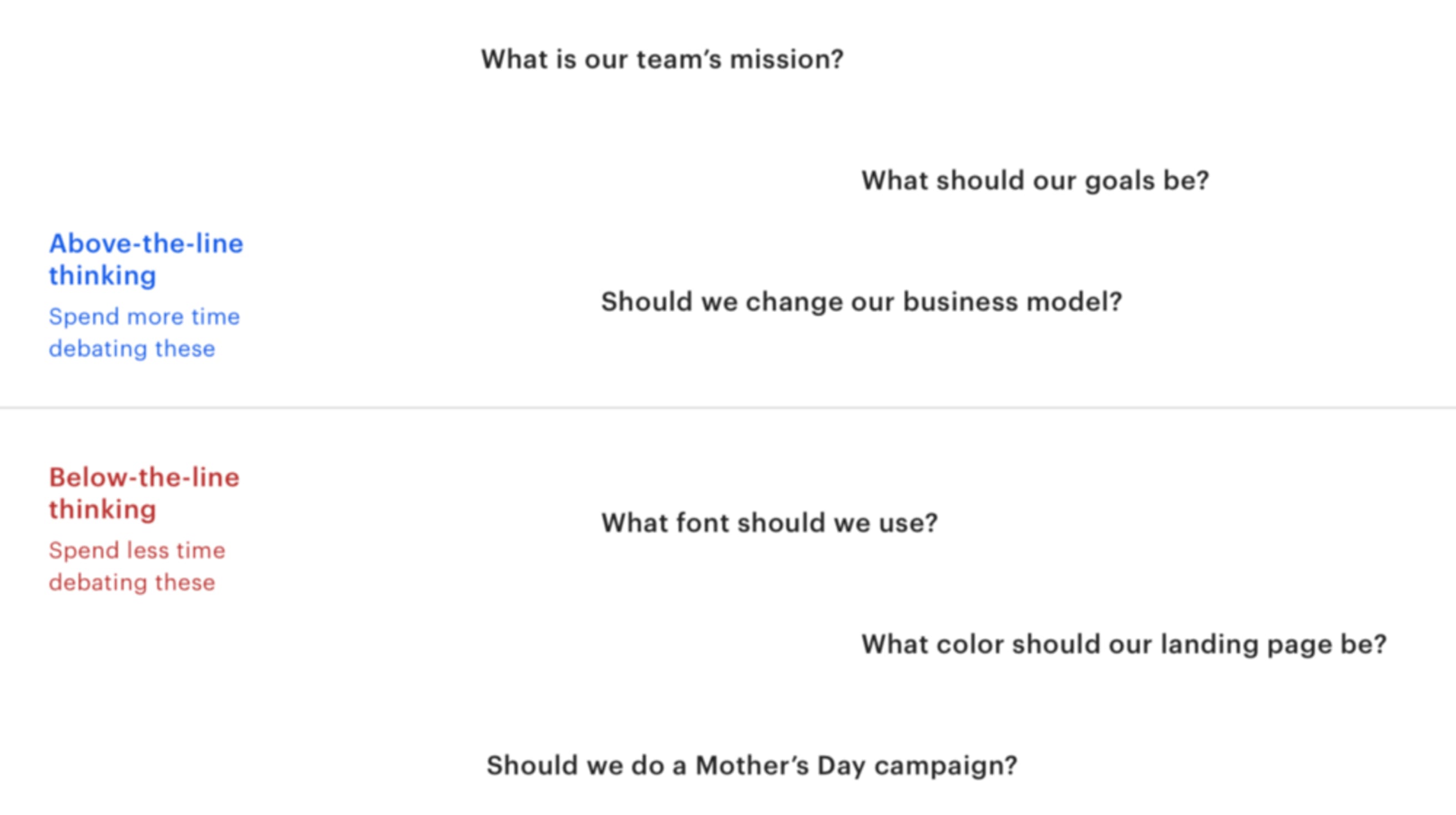

In other words, while the two parties might agree on almost everything, they make a bigger scene about the small details they don’t agree on. Dalio refers to this as above the line and below the line thinking. Above the line thinking is concerned with broader concepts and general direction. Below the line thinking focuses on the finer details — what colors to use in the email, which department should build the landing page, etc. Both are important, but it’s helpful to distinguish whether your disagreement surrounds big picture items or implementation details. The latter is less important than the former.

When faced with a major decision, both parties should ideally agree on the overall direction and big picture items. For example, if you’re pivoting the entire company to focus on a new problem, your leadership team should all be onboard with the new mission. But they don’t all need to agree on the specific implementation for that new vision. For example, the head of marketing and the head of engineering don’t need to see eye to eye about the new logo; that’s below the line.

When faced with a disagreement, circle back to the core ideas and see if both parties can agree on those first. If the remaining disagreements are all about below the line items, defer to the individual with the most knowledge and experience in the particular area and move forward. Dalio refers to this as “believability weighted decisions.” At Bridgewater, all opinions are not weighted equally. Individuals with more demonstrated experience and a proven track record in a specific area hold more weight. If there’s a stalemate, their opinions ultimately form the decision.

Do the work required to have an opinion.

Investor and businessman Charlie Munger has made hundreds of multi-million dollar decisions in his lifetime. As one of the wealthiest and most respected investors in the world, it would be easy for Munger to hold resolutely to his opinions even when others disagree. Instead, he does the exact opposite:

“I never allow myself to have an opinion on anything that I don’t know the other side’s argument better than they do.”

To borrow a phrase from Shane Parrish at Farnam Street, Munger does the work required to have an opinion.

“Doing the work means you can’t make up your mind with a high degree of confidence right away. Doing the work forces you to challenge your beliefs because you have to argue from both [sides]. You become the somewhat impartial judge. What’s on trial is your opinion.”

Far too often, we enter a disagreement with a rock-solid understanding of our side yet little understanding of the opposition. How do we escape our own bias?

A simple way is to take fifteen minutes, an hour, a day, or even a week depending on what’s really at stake, and ask yourself, “What if I’m wrong?”. Gather facts and details that support the opposite point of view. Break down your arguments individually and try to create counterexamples. By setting aside time to ask yourself, “What if I’m wrong?” you’re either going to strengthen your argument by anticipating questions, or you’re going to learn something new and take a more nuanced position.

A second, more extreme way to reveal your own blind spots is a tactic called “red teaming.” Essentially, it’s stress testing your ideas in a group setting, and it’s used by individuals like Marc Andreesen (well-known investor in Silicon Valley) and Stanley McChrystal (retired four-star general from the U.S. Army). McChrystal describes how red teams work in Tools of Titans by Tim Ferriss:

“What happens is, as you develop a plan — you’ve got a problem and you develop a way to solve that problem — you fall in love with it. You start to dismiss the shortcomings of it…So red teaming is: You take people who aren’t wedded to the plan and [ask them,] ‘How would you disrupt this plan or how would you defeat this plan?’”

The best case scenario is that you can “red team” your own ideas because you understand the counterpoint so well. But when a really important decision is on the line it’s a good idea ask others to help stress test your thinking with you.

Are you actually listening to the other side?

If you’ve ever found yourself in a disagreement, this situation from Ury will sound familiar:

“Too often negotiations proceed as follows: Party A sets out their opening position. Party B is so focused on figuring out what they will say that they don’t really listen. When Party B’s turn comes to lay out their position, Party A thinks, “They didn’t respond to what I said. They must not have heard me. I’d better repeat it.”

When we get worked up in conversation, we become so focused on exactly what we’re going to say that we don’t spend the time necessary to understand the counterargument and listen to the other party.

There are several downsides to this approach, but the most obvious one is that the other party doesn’t feel heard at all. They feel as though their argument is falling on deaf ears. In a podcast with Tim Ferriss, entrepreneur Stewart Brand recounts the time he spent working on California Governor Jerry Brown’s campaign. Brand would watch Brown interact with protesters at various events, and through his interaction, he would demonstrate the power of listening. As Brand recalls:

“Jerry would see the protesters and immediately head over to talk to them. He’d ask what’s on their mind. Then, he would say, ‘I think I got it. Let me see if I got it.’ Then, he would say back to them their stance often better than they had stated it, and you would see them just melt. Because the thing they wanted to have happen was for him to be aware of their position and to understand it and he’d just showed that he’d done that.”

It’s easier than you might think to demonstrate that you’re listening to the other side in a disagreement. Take a page out of Governor Brown’s book: Reframe their position and ask for confirmation that you have it right. You might say, “Just to make sure I understand, it sounds like your main frustration is…Is that right or am I misunderstanding?”

Regarding listening, Karl Weick had it right with this phrase: “Fight as if you’re right. Listen as if you’re wrong.”

Present your ideas inclusively, not combatively.

Disagreements can create an “us versus them” mentality with clear winners and losers. One path forward is to double down on your position and hope you come out a winner.

A better approach is to ditch the entire notion of winners and losers. Instead, you’re both on the same team working toward a better solution. As Ury explains:

“The standard mindset is either/or: Either you are right or the other side is. The alternative mindset is both/and. They can be right in terms of their experience, and you can be right in terms of yours.”

Ury elaborates on one way to establish this inclusive mindset. Instead of starting your counter argument with “but,” start with “yes…and.” Instead of saying this:

“I understand you want to make sure we’re spending our money wisely on ads, but TV offers such a huge audience I think we would be insane not to go for it.”

You could say this:

“Yes, we definitely need to make sure we’re maximizing the return on every dollar spent. And according to my research, the potential audience from TV ads matches our demographics better than social media so it feels like a worthwhile tradeoff.”

The former creates opposition using the word “but.” At the end of the statement, it’s clear that we’re on two different sides. The latter is more inclusive since we’re starting with “yes,” reframing the pieces we do agree on, and then presenting our counterpoint as an addition.

When faced with the discomfort of disagreement, our basic human instincts often lead us astray; we either fight tooth and nail for our point of view or turn tail and avoid it altogether. There are more constructive ways:

Set your pride aside.

Maintain perspective on what’s really important.

Genuinely listen to the other side.

Do the work to have an opinion.

Frame your point of view inclusively, not combatively.

It’s the harder way, but it’s worth it. If we could all learn to disagree a little more gracefully, the world would be a much better place.

Great teamwork starts with great communication. See how Twist helps teams of all kinds get there.