When in doubt, Google it.

This is my first instinct whenever I face a problem I don't know enough to solve. As a Millennial, I can barely remember the Internet before Google made the vast collective knowledge of the Web readily accessible for any whim or query that crossed my mind.

Though we've never had more access to high-quality information to help us make those decisions, it hasn't made decision-making any easier. We can now research the pros and cons of each and every option available to us. A simple search query can often open a time-sucking black hole of link clicking that can end hours later, making me more confused than ever about the right action.

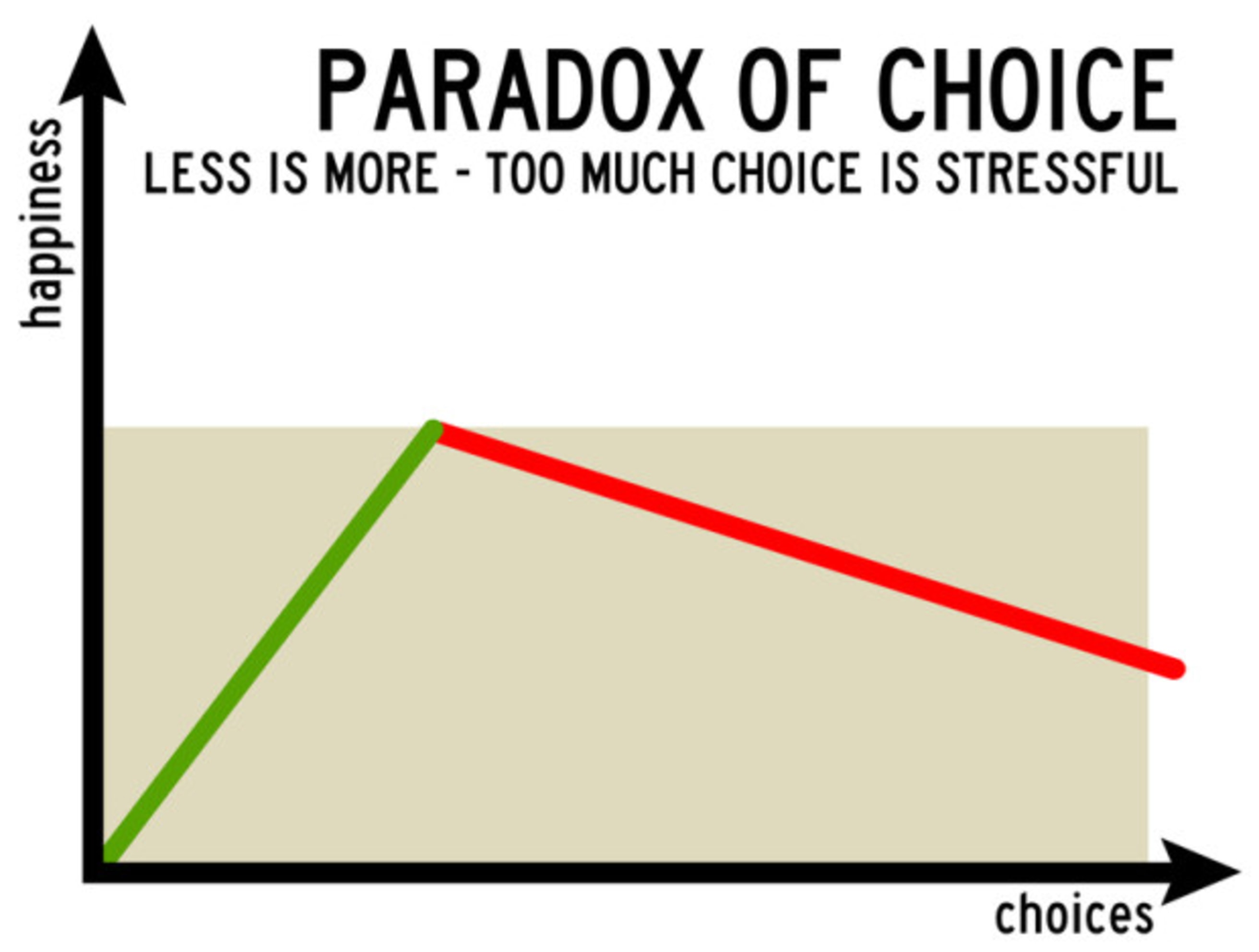

Psychologist Barry Schwartz coined the phrase "Paradox of Choice" to describe his consistent findings that, while increased choice allows us to achieve objectively better results, it also leads to greater anxiety, indecision, analysis paralysis, and dissatisfaction.

Rather than empowering us to make better choices, our virtually unlimited access to information often leads to greater fear of making the wrong decision, which in turn leads to us spinning our wheels in a seemingly inescapable purgatory of analysis paralysis, all the while getting nowhere on our important projects.

(Ironically, a quick Google search of "analysis paralysis" pulls up no less than 1,330,000 resources.)

For this article, I wanted to find out what exactly goes on in our brains when we experience chronic indecision and - most importantly - what we can do about it.

How overthinking decisions holds you back

Delaying action while over-analyzing information clearly doesn't help when it comes to getting things done. In fact, a 2018 IDC study showed that, on average, employees spend more than half their week receiving and managing information rather than using it to do their jobs!

Unfortunately, that's just the start of the bad news. Studies in psychology and neuroscience reveal that analysis paralysis takes a far greater toll on your productivity and well-being than just lost time.

Here are four not-so-obvious ways that overthinking your decisions is holding you back:

1. Overthinking lowers your performance on mentally-demanding tasks

Our working memory is where the magic happens when it comes to high-level cognitive tasks like learning. As psychologists Sian Beilock and Thomas Carr describe, it's "a short-term memory system that maintains, in an active state, a limited amount of information with immediate relevance to the task at hand while preventing distractions from the environment and irrelevant thoughts...If the ability of working memory to maintain task focus is disrupted, performance may suffer."

In short, our working memory allows us to focus on the information we need to get things done at the moment we're doing them. But, unfortunately, our working memory is in limited supply. You can think of it like our brain's computer memory. Once it's used up, nothing more can fit in.

Studies have repeatedly shown that high-pressure, anxiety-producing situations lead to lower performance on cognitively demanding tasks - the tasks that rely most heavily on working memory. Furthermore, the more participants want to perform well on a task, the more their performance suffers. Researchers think that both anxiety and pressure generate distracting thoughts about the situation that takes up part of the working memory capacity that would otherwise be used to complete the task.

When you overanalyze a situation, the repetitive thoughts, anxiety, and self-doubt decrease the amount of working memory you have available to complete challenging tasks, causing your productivity to plummet even further.

2. Analysis paralysis kills your creativity

A recent Stanford study suggests that overthinking impedes our ability to perform cognitive tasks and keeps us from reaching our creative potential.

Grace Hawthorne, a professor at Stanford University Institute of Design, teamed up with behavioral scientist Allan Reiss to find a way to scientifically measure creativity using brain imaging:

"Participants in the study were placed into a functional magnetic resonance imaging machine with a nonmagnetic tablet and asked to draw a series of pictures based on action words (for example, vote, exhaust, salute) with 30 seconds for each word. (They also drew a zigzag line to establish baseline brain function for the task of drawing.) The participants later ranked each word picture based on its difficulty to draw. The tablet transmitted the drawings to researchers at the d.school who scored them on a 5-point scale of creativity, and researchers at the School of Medicine analyzed the fMRI scans for brain activity patterns.

The results were surprising: the prefrontal cortex, traditionally associated with thinking, was most active for the drawings the participants ranked as most difficult; the cerebellum [the part of the brain traditionally associated with movement] was most active for the drawings the participants scored highest on for creativity. Essentially, the less the participants thought about what they were drawing, the more creative their drawings were.”

These findings suggest that overthinking a problem makes it harder to do your best creative work.

3. Overthinking eats up your willpower

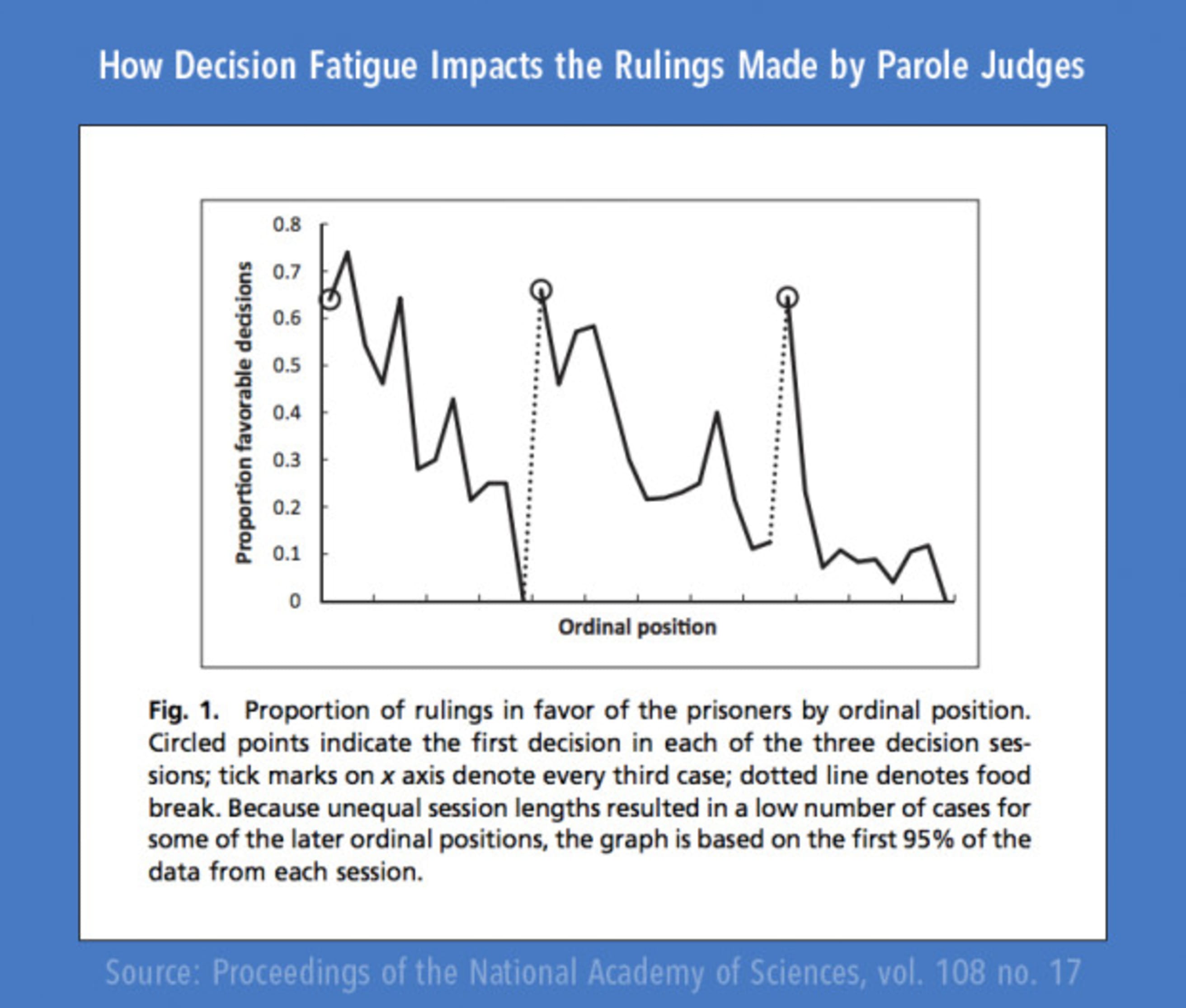

A fascinating (and rather alarming) study published by the National Academy of Science looked at the decisions of parole board judges over a 10-month period. They found that judges were significantly more likely to grant parole earlier in the morning and immediately after a food break. Cases that came before judges at the end of long sessions were much more likely to be denied. This phenomenon held true in over 1,100 cases regardless of the severity of the crime.

What explains these surprising findings? The judges were experiencing what psychologists call decision fatigue. Each decision that we make, from whether or not to hit snooze to what outfit we'll wear to what we'll eat for lunch, draws on the same limited supply of willpower. You can think of willpower as a muscle. The more you use it, the more it wears out, leaving you feeling overwhelmed and exhausted. That's why so many dieters start out strong at the beginning of the day with a healthy breakfast and lunch, only to succumb to the temptations of junk food from the office break room in the afternoon.

Actions that we take automatically, like brushing our teeth, take little willpower. However, when we agonize over a decision, we deplete our limited supply of willpower much more quickly, causing us to feel exhausted and overwhelmed.

Not only does this decision fatigue inhibit our ability to assess the situation at hand clearly, but it also makes us more likely to choose unhealthy food, skip exercise, and put off working on side projects in favor of watching TV. In short, over-analyzing a decision makes it much more difficult to make high-quality, long-term choices later on.

4. Analysis paralysis makes you less happy

In 1956, economist Herman Simon created the term "satisficer" to describe the decision-making style that 'prioritizes an adequate solution over an optimal solution'. As Gretchen Rubin of The Happiness Project describes, "Satisficers make a decision once their criteria are met; when they find the hotel or the pasta sauce that has the qualities they want, they're satisfied."

In contrast, "Maximizers want to make the best possible decision; even if they see a bicycle that meets their requirements, they can't make a decision until they've examined every option."

Research suggests that whether you're a satisfier or a maximizer can have a huge impact on your happiness and well-being. Four different studies carried out by Swarthmore College studied the psychological effects of these two decision-making styles. They found that:

- Maximizers reported significantly less life satisfaction, happiness, optimism, and self-esteem, and significantly more regret and depression, than satisficers.

- Maximizers were more likely to engage in social comparison and counterfactual thinking (i.e., What if I had chosen option number 2 instead?). They experienced more regret and less happiness after making a consumer decision.

- Maximizers experienced a greater increase in negative mood when they did not perform as well as their peers.

Though analyzing every last option in the quest for the best choice may lead to an objectively better outcome in some situations, maximizing ultimately leads to more anxiety and regret and less happiness and satisfaction with your decisions.

Simple ways to stop analysis paralysis and start doing:

Ok, so we know from science and experience that overthinking a decision increases anxiety and kills your productivity, but what can we do about it? Below are a few science-backed, expert-approved strategies that you can start using today to end analysis paralysis, make decisions efficiently, and ultimately get more done with less stress.

1. Structure your day for the decisions that matter most.

Not all decisions are created equal. Clearly, deciding on what toothpaste to buy or what to make for breakfast are less worthy of deliberation than determining a strategic direction for your company. Because our ability to make quality, long-term decisions deteriorates with each additional choice we make, big or small, the most successful people structure their day to cut down on the number of decisions they'll need to make. They tackle their most important task first thing in the morning when their willpower reserves are at their fullest and try to make small decisions as automatic as possible. President Obama famously wears the same exact suit every day to conserve mental energy and willpower for more important decisions later in the day.

Don't try to tackle big decisions in the afternoon. If you find yourself getting caught in a downward spiral of analysis paralysis late in the day, put aside everything and work on an unrelated task. Or simply call it quits for the day. Come back to it in the morning with a fresh perspective and replenished willpower reserves. Try a productivity method like Eat the Frog so you can tackle your most important, impactful tasks first.

Eliminate as many decisions as possible by turning them into habits that take little conscious thought to complete. Build strong habits and routines into your day as a way to conserve willpower for more important decisions.

2. Intentionally limit the amount of information you consume.

For any problem we face, there is a virtually limitless supply of information we could delve into. I currently have 35 different tabs open for this article (well, mostly for this article), and that's not even counting the windows I have open for other apps. That's why it's important to approach the research with intention.

As an attorney, a government official, a law school professor, a business school professor, and a prolific author, Bob Pozen gets an incredible amount done in the day. One of the secrets to his productivity is to efficiently manage information by determining what he wants to learn from it first, then reading for that specific information. Reading with a specific goal in mind allows him to get through large amounts of information without getting overwhelmed.

Another way to consume information without getting lost in analysis paralysis is to set a volume limit whenever doing research. Determine the number of resources you'll use first. Make this strategy even more effective by limiting yourself to only those number of tabs.

Hat tip to Buffer's co-founder Leo Widrich for this productivity tip– he increases his focus and efficiency by creating a single-tabbing habit. Every night, Leo writes out a to-do list with only the most important tasks that need to get done the following day. Then he plans single-tab browsing to align with those tasks and only those tasks.

3. Set a deadline and hold yourself accountable.

Parkinson's Law states that work expands to fill the amount of time you've allotted it. If you give yourself an hour to do a task, it will take an hour. If you give yourself 15 minutes to complete the same task, it will take 15 minutes. The same holds true for making decisions. Setting a time constraint can force you to prioritize or make a decision more efficiently.

The catch is it's extremely difficult to trick yourself into believing that self-imposed deadlines are real. (Believe me, I've tried.) Find a way to hold yourself accountable to your deadlines. Beth Belle Cooper wrote a fantastic piece on the Zapier blog on how to stop missing deadlines. My favorite piece of advice: make your deadline as public as possible. Tell a coworker or friend who will help to hold you accountable to your decision deadline, or even commit to a deadline on social media.

4. Know your main objective.

Self-improvement blogger Celestine Chua has found that identifying and staying true to one main objective as the basis for decision-making helps her overcome a tendency to overthink.

"Many people often want to collaborate with me in my business. From promoting their products, to promoting their campaigns, having me create a course for their portal, to creating a new offering together, these are examples of pitches I get every week.

My criteria for this decision is simple: exposure for PE. Will I gain any exposure for PE from this engagement? is the question I ask myself. If the answer is “no” and they are simply trying to get free exposure with minimal/no contribution on their end, then it’s usually a “no” — short and simple. It doesn’t matter the big numbers they quote (e.g., “We have over 30 top bloggers working with us”), the high gains they project from this collaboration (e.g., “We anticipate thousands of customers”), and how “big wig” they are (e.g., “I’ve appeared on New York Times before”); none are as important as expanding PE’s exposure to me.

In knowing my end objective, it helps me to be quick and decisive since I can immediately assess the option that’ll help me to realize my end goal."

Similarly, Brenna Loury, CMO at Doist, has a recurring task to remind her to review our top five marketing goals as a company at the start of every workday. As a result, our main goals are always top of mind when she needs to decide what to prioritize or when faced with a difficult business or marketing decision. Anything that doesn't align with our current goals gets postponed or eliminated.

What's the most important thing for you personally and professionally? It could be a concrete goal (e.g., growing my email list) or a central value that you want to live out in your life (e.g., health, friendship, family). Now write it down and find a way to remind yourself to review it regularly. When you encounter a tough decision, avoid analysis paralysis by asking yourself which option aligns best with your most important goal or value.

5. Get out of your own head and talk it out with someone else.

In a TED Talk titled "Why we make bad decisions", psychologist Daniel Gilbert explains the cognitive biases that make us terrible at making rational decisions and predicting the choice that will make us happiest in the long run.

“People have been shown to overestimate how unhappy they will be after receiving bad test results, becoming disabled or being denied a promotion, and to overestimate how happy they will be after winning a prize, initiating a romantic relationship or taking revenge against those who have harmed them."

In fact, studies have shown that other people, even complete strangers, are better at predicting our future satisfaction with a particular decision than we are ourselves.

"In many domains of life, the experience of one randomly selected other person can beat your own best guess by a factor of two… We all like a trip to Paris better than gallbladder surgery; everybody would rather have a compliment than have their thumb nailed to the floor. The differences between you and other people are so unimportant that you would do better predicting how you are going to like something simply by asking one randomly chosen person how they like it."

When paralyzed by a particular decision, reaching out for someone else's opinion, literally anyone else's opinion, can lead to a decision we're happier with than if we had made the choice ourselves.

The next time you catch yourself thinking over a particular issue again and again, schedule a meeting with a coworker, supervisor, mentor, or friend. Having to present your deliberations to someone else forces you to synthesize the information you've been collecting in a clear, concise way (or at least more clear and concise than when it was all bouncing around in your own head). In addition, having outward validation of your ideas from someone whose opinion you respect can be just what you need to overcome self-doubt and build the confidence to take action.

6. Approach problems with an iterative mindset.

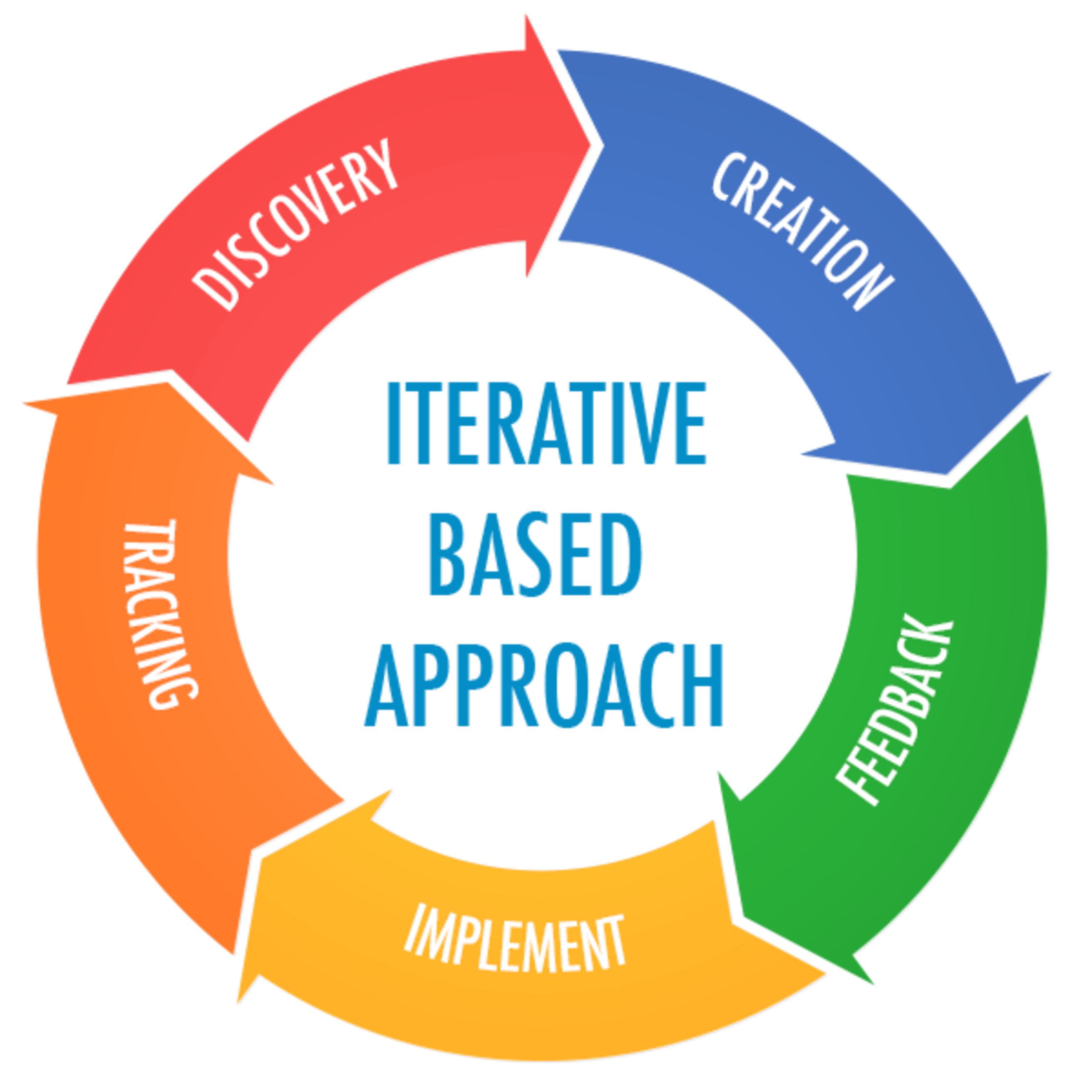

Decisions are most difficult when uncertainty is the greatest. We often base our choices on assumptions that may or may not be accurate. We try to compensate by digging further and further into research, but more often than not, the only way to know if our assumptions are correct is by actually taking action.

Luckily, there's an easy way to test our assumptions without having to commit to any given path fully. It's called an iterative approach. This concept is most associated with software development, particularly at fast-moving start-ups with few resources.

Here's the basic idea:

Despite extensive customer research and interviews, a company can never know exactly how its target audience will use (or not use) a new product or feature. Instead of wasting time trying to release a perfect version of a product that may or may not fit customers' needs, a company following an iterative approach would focus on producing a "minimum viable product."

Getting an imperfect product out as quickly as possible allows a product team to use data and user feedback to test assumptions, identify what works and doesn't work, and incorporate those learnings back into future versions or iterations of the product.

Productivity and mindfulness expert Leo Babauta adopted an iterative approach to writing his book, Writer as Coder. Here's what his workflow looked like:

- Write a minimum viable book for alpha testers

- Get feedback, and improve.

- Iterate quickly on their feedback.

- Take the ideas to a larger group.

- Use all the feedback to write the book.

- Keep getting feedback and iterating even after the book is written.

Using this approach, Leo found that by using an iterative approach, he was more motivated to write, wrote the book more quickly, and ultimately created the final product that was more helpful and successful than if he had written the book in isolation.

We can also reap the benefits of the iterative approach to break the gridlock of analysis paralysis. Viewing a decision as final raises the stakes and causes us to get stuck trying to find the perfect solution. In contrast, viewing each decision as an experiment to be tested gives us the freedom to choose something quickly because we know we can improve upon it later. Not only is iterative decision-making faster, but it can also lead to better outcomes as our experiments test and tweak our decisions in the real world.

7. Start before you feel ready.

James Clear gives perhaps some of the greatest advice for overcoming paralysis and taking action toward your goals: take a cue from Richard Branson and start before you feel ready.

"Branson has started so many businesses, ventures, charities, and expeditions that it’s simply not possible for him to have felt prepared, qualified, and ready to start all of them. In fact, it’s unlikely that he was qualified or prepared to start any of them. He had never flown a plane and didn’t know anything about the engineering of planes, but he started an airline company anyway. He is a perfect example of why the “chosen ones” choose themselves.

You’re bound to feel uncertain, unprepared, and unqualified. But let me assure you of this: what you have right now is enough. You can plan, delay, and revise all you want, but trust me, what you have now is enough to start. It doesn’t matter if you’re trying to start a business, lose weight, write a book, or achieve any number of goals… who you are, what you have, and what you know right now is good enough to get going."

Collecting and analyzing more and more information is a tempting way to try and overcome the uncertainty that comes with taking on big goals. It's easy to trick ourselves into thinking we're making progress. In the end, action is what decides our ultimate success or failure. So the next time you're stuck in analysis mode, remember that successful people start before they feel ready and figure the rest out on the way.

8. Make your decision the right one.

It's tempting to believe that the best decision exists and that we can figure out what it is by just researching deeper and thinking harder. The truth is that the options in front of you may be equally valid. You may never be able to determine which is the best choice.

All too often, we forget that making the decision is only the first step. Ed Batista of the Stanford Business School put it this way in his article for Harvard Business Review:

"Before we make any decision — particularly one that will be difficult to undo — we’re understandably anxious and focused on identifying the “best” option because of the risk of being “wrong.” But a by-product of that mindset is that

we overemphasize the moment of choice and lose sight of everything that follows. Merely selecting the “best” option doesn’t guarantee that things will turn out well in the long run, just as making a sub-optimal choice doesn’t doom us to failure or unhappiness. It’s what happens next (and in the days, months, and years that follow) that ultimately determines whether a given decision was 'right.’"

It's often our confidence in and commitment to our decisions that determine whether they are the "right" ones in the end. When faced with a difficult decision, ask yourself which option you'll be more motivated to make succeed. Instead of getting stuck in analysis paralysis, use your time and energy it coming up with a concrete, actionable plan to make your decision succeed.

If you enjoyed this article, you may want to read Paralyzed by Perfectionism? Try Rethinking Your To-Do List.